The decline of Elis and its gradual abandonment occurred in Late Antiquity, brought about by natural disasters and repeated invasions of barbarian tribes. Yet the decisive blow came with the rise and establishment of Christianity under the Byzantine emperors. The new religion led to the discrediting and eventual abandonment of the Sanctuary of Olympia – with which Elis was inextricably linked – marking, by the 7th century AD, the end of the city itself.

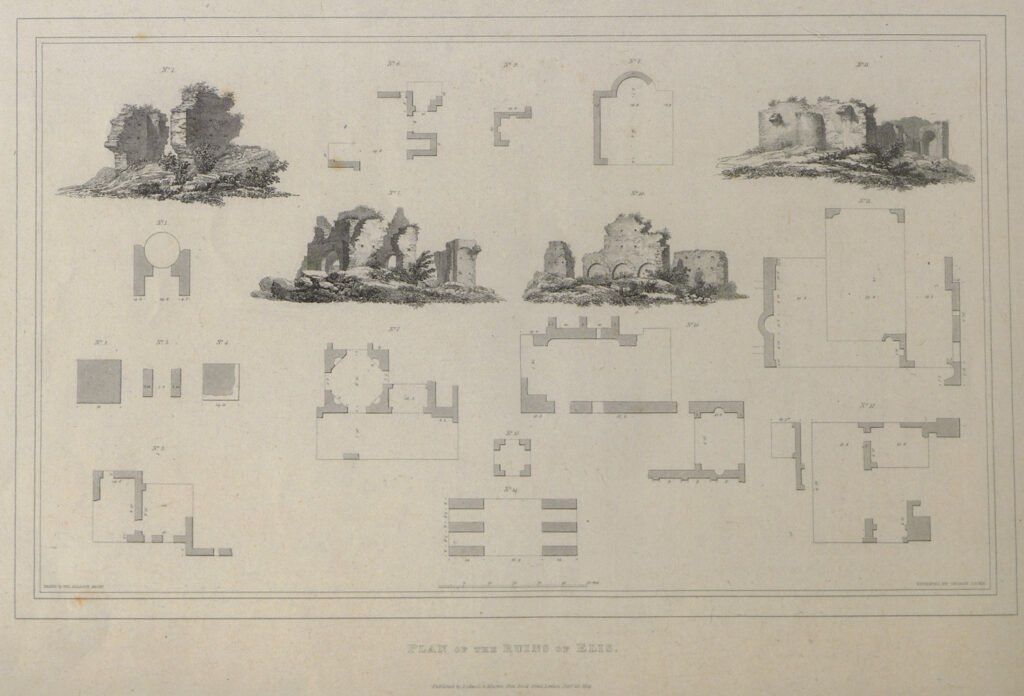

In the centuries that followed, the ruined remains of the ancient city were slowly buried beneath the deposits of the river Peneios. Only a few structures, scarred by time, remained visible – silent witnesses to the city’s former prominence in the fertile valley.

Down to more recent times, the surviving ruins provided valuable building material for the inhabitants of the region. Stones, columns, and architectural fragments from ancient Elis were reused in the construction of houses and buildings in neighboring villages (Kalyvia, Avgeio, Chavari, Agios Dimitrios, etc.) as well as in towns such as Amaliada and Gastouni.

STANHOPE, John Spencer. Olympia; or, Topography illustrative of the actual state of the Plain of Plympia, and of the Ruins of the City of Elis, London, Dodwell and Martin, 1824/ Athens, 2010. Πηγή: Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation

The extensive and fertile land once occupied by the city, after its abandonment and ruin, was gradually reclaimed for cultivation by the surrounding communities. Yet the traces of Elis’ glorious past never vanished entirely; scattered ruins continuously bore witness to its enduring legacy.

Love and admiration for antiquity – and especially for the finds linked to the city that had the honor of permanently hosting the ancient Olympic Games – meant that many of these objects were regarded as treasures. From the early modern era onwards, however, numerous artifacts found their way, often by means we would now call illicit, into private collections and later into the great museums of Europe.

For the local inhabitants during the Ottoman period, most of whom had little or no formal education, the discovery and sale of antiquities – particularly the finely crafted coins of Elis and other artifacts of the past – became an accepted source of income that contributed to their survival.